Writer & Visual Artist

Nickel Eclipse is a merging of personal and cultural history. Structured in part like the alternating colored beads on a wampum belt, patterns emerge from this exploration of contemporary life on an eastern Indian reservation and the sometimes tenuous persistence of a culture after centuries of survival within another, more dominant, culture. The poems, while highly personalized, reflect the tension of speakers surviving within-though never fully of-that larger culture, where lives are formed and meaning defined by their inherent separateness.

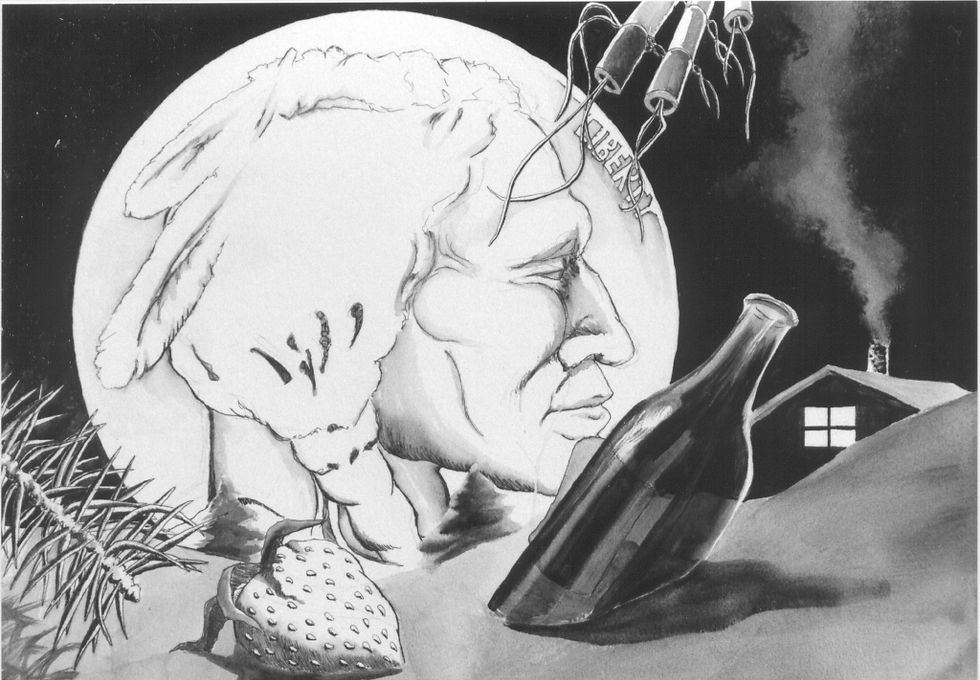

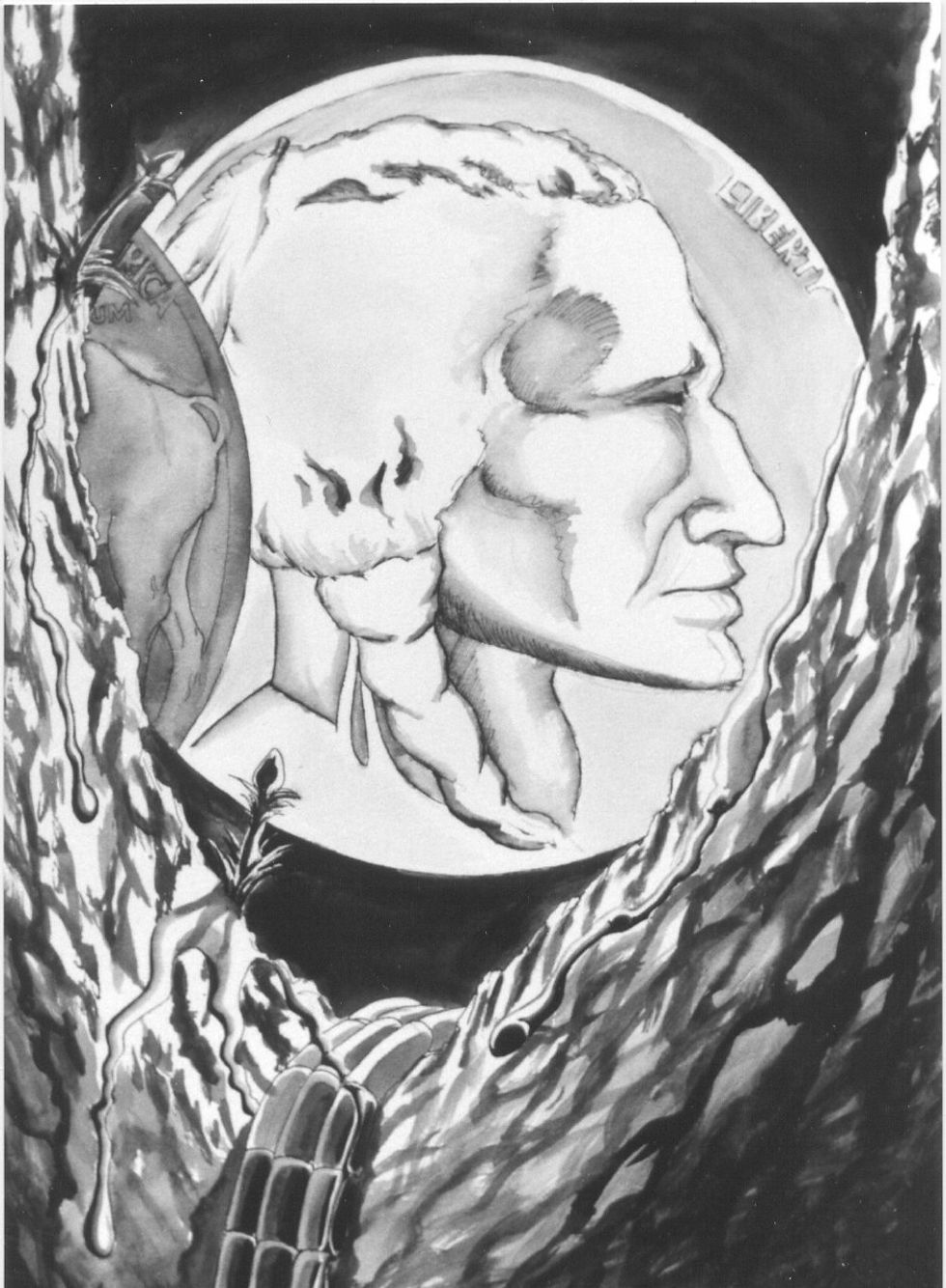

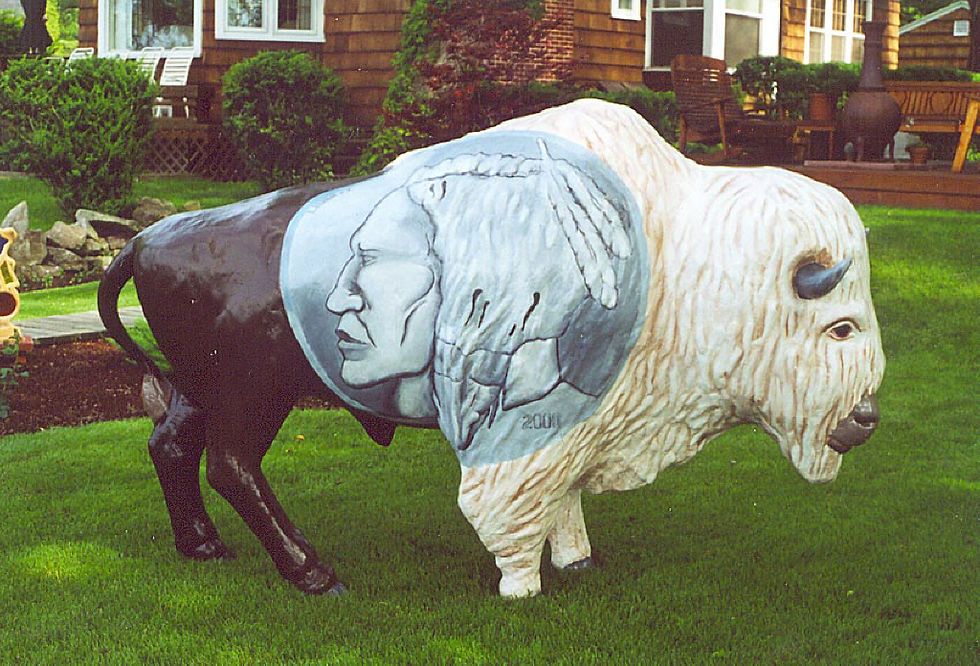

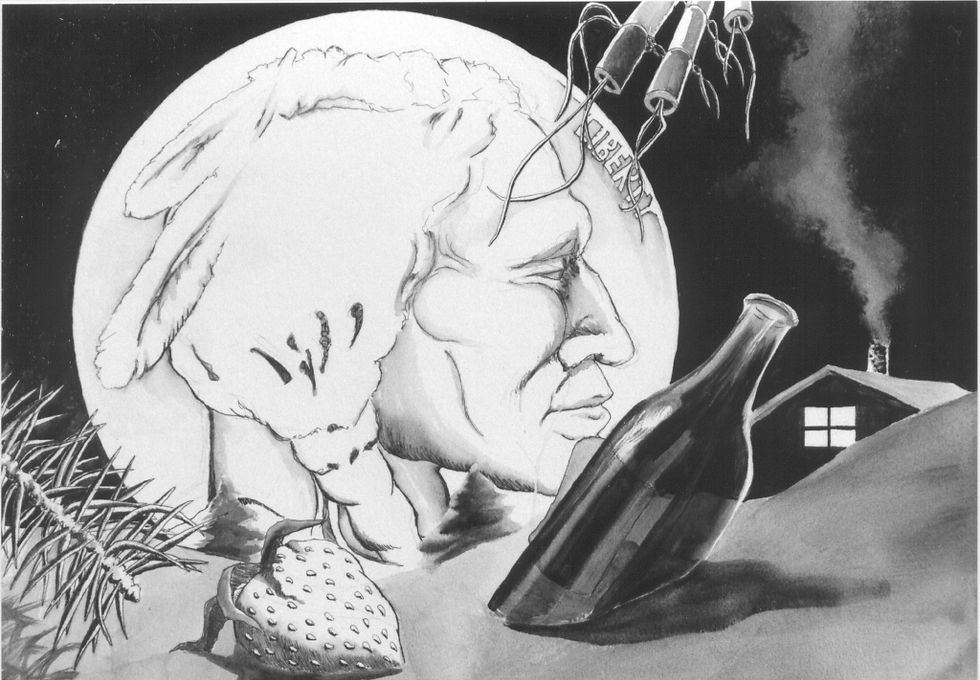

Gansworth's paintings complement the poems, using the metaphor of the cycle of moons identified in the traditional Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) culture's calendar. These paintings of the different lunar phases serve to organize the poems around a common image, breaking them into sections through the use of an eclipse. Additionally, the relationships indigenous communities have had with the United States-from thriving to near extinction to eventual re- emergence-are symbolized in the progression of that eclipse across the moon.

Symbols common to the culture appear throughout the cycles: the Three Sisters (Corn, Beans, and Squash), Strawberries, and Green Corn, from the ceremonies named for them, and more consistently, wampum beads-within which Haudenosaunee culture is iconographically documented-appear in various incarnations, from the earliest shell groupings, through isolated shaped beads, small strings, and full- belt formations.

Reviews:

Eric Gansworth skips words across the ocean, casts a line that won't stop till all fish are hooked (tenderly-we are the fish!). Nickel Eclipse is a language river that doesn't stop till the poem comes to rest, often a single sentence, into itself. Near as I can tell, he invented this Sentence Form: a single thought curling, moving to its somehow inevitable period some twenty lines later. Try "The Reservation Knows Your Name As Well As I"(sometimes his titles stretch out too), and "Flight" (sometimes not), and see how twisty language can be. Gansworth's clarity and chill ability assures you'll never get lost.

What you'll come away from Nickel Eclipse with will include:

1. Living through Indian oppression with anger that burns but never rhetoricizes.

2. An omniscience reminiscent of viewing Earth from moon(s).

3. A never-ending story-telling that includes characters like Jonathan Edwards, Joy Harjo, Jerry Garcia, Jane Fonda, Russell Means, Marc Chagall, locations from Muscogee to Tuscarora to Seneca, the Human Condition on the Rez, at Lincoln Center, in Spanish classes in Texas.

It's a recipe that, when coupled with Gansworth's delirious love of words and forms, spins this book into literary orbit. His generosity and gentility keep it there, a steady presence. The riches of Nickel Eclipse will shine on you, stay with you. Eric Gansworth is the Man Behind the Man in the Moon.

Bob Holman,

author of The Collect Call of the Wild

The year in Indian Country is divided into thirteen moons. Thirteen equal cycles of four weeks, twenty-eight days. The Sugar Moon, Fishing Moon, and the Very Cold Moon are examples denoting the seasons and their seasonal activities in the Iroquois calendar.

It is in this framework that Gansworth has chosen to set the structure of his book of poems. The use of the eclipse metaphor represents the waxing and waning and waxing of Indian life in these post-contact times. The eclipse also denotes the (albeit temporary) advent of Western civilization over Indian culture. An Indian world that now includes elements of that Western contact, fragments of contemporary culture, and religion indelibly wedded to the modern Indiancoffee, cigarettes, and the movies being as Indian nowadays as sage, sweetgrass, and long hair on both men and women. The Indian-head nickel is a prime example; the dominant cultures currency emblazoned with an Indian profile and a buffalo. Things are forever and hopelessly mixed up, like a good batch of corn soup. The most Indian trait of all is to make-do with whatever is available.

Strong, full of the humorous irony that Indian life is famous for, these poems present an uncommon slice of American life. In a poem entitled Wine and Cheese the chasm between White and Indian is navigated. Mike and me / two reservation boys / in a plush, carpeted living room / (some friend of his from school) / need to be told / to use coasters (having thought they were / small decorative petrified / wood pieces) / when placing the crystal / long-stemmed wine goblets / on the glass-top coffee table.

Through these poems Indians are seen as they are now, a living, changing, vital culture. Gansworth provides Indian time and war ponies, reservation magic and witchcraft, mystery and gritty cold walks to the outhouse. In a poem subject that is deeply and personally entrenched in Indian life, On Meeting My Father in a Bar for the First Time, he makes something that is not at all humorous seem somehow inexplicably normal. Sidling up to some / potentials, I nod / and smile that smile / which will buy me / at least a draft. His words echo a familiar chorus heard before in Indian Country.

Gansworth offers an agile and fluent dance of language that keeps readers tight in the drums circle. Meanwhile he debunks the mystical realm some well-meaning white people would like to relegate Indians to, I dont know any Indians / who wear crystals / around their necks. (December)

ForeWord Magazine